2021

There is no Creative Director School

The Creative Director role is ill-defined across many industries and, as a result, inaccessible. Let’s change that.

☻ This in-progress essay is part of a series of writing, interviews, and syllabus for emerging creative leaders. For more information please get in touch ©2021 August Heffner

Background

Creative Directors from around the world exhibit vast differences and striking similarities in how they see their role and how they came to their profession. As most Creative Directors are in the service of solving problems, the ideas of challenge and overcoming obstacles run deep. Over the past year I’ve interviewed 15 Creative Directors on 3 continents. They work in fashion, branding, advertising, and digitial product design. They’ve helped me create a set of essays and experiments to help myself and others, see their value in their work as they move from Independent Contributor to less-well-defined roles in creativity. This page is the start of many more specific explorations.

01

To start, let’s reexamine our focus on our “subjects,” be them apparel design, graphic design, copywriting. Our focus on our “subjects” is imperative for understanding. But what does it mean for creativity? Can this subject-focus suppress creativity and even encourage ambiguity around creative professions? The leaders I’ve spoken to have come up in fashion, user experience, advertising, and skateboarding, but all agree they moved beyond the constraints of their original “major.”

02

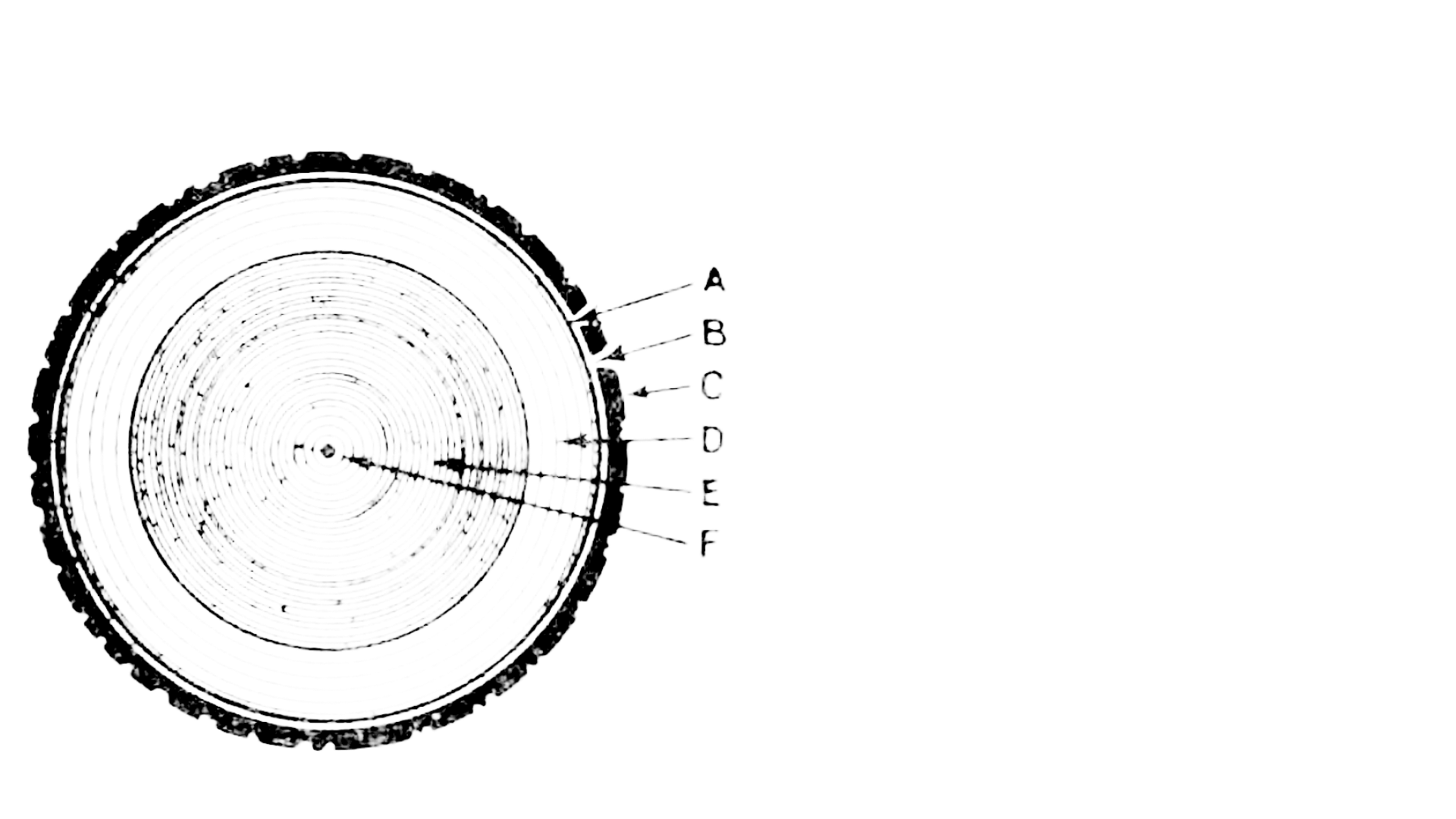

In the creative industry we’ve reduced practice to specialization in these “subjects” — expecting only limited awareness of surrounding inputs. For example, the visual design community (from graphic design to digital product design) can often use a “T-shaped” method in evaulation (depicted below) where a designer’s focus is the anchor while other subjects become peripheral.

03

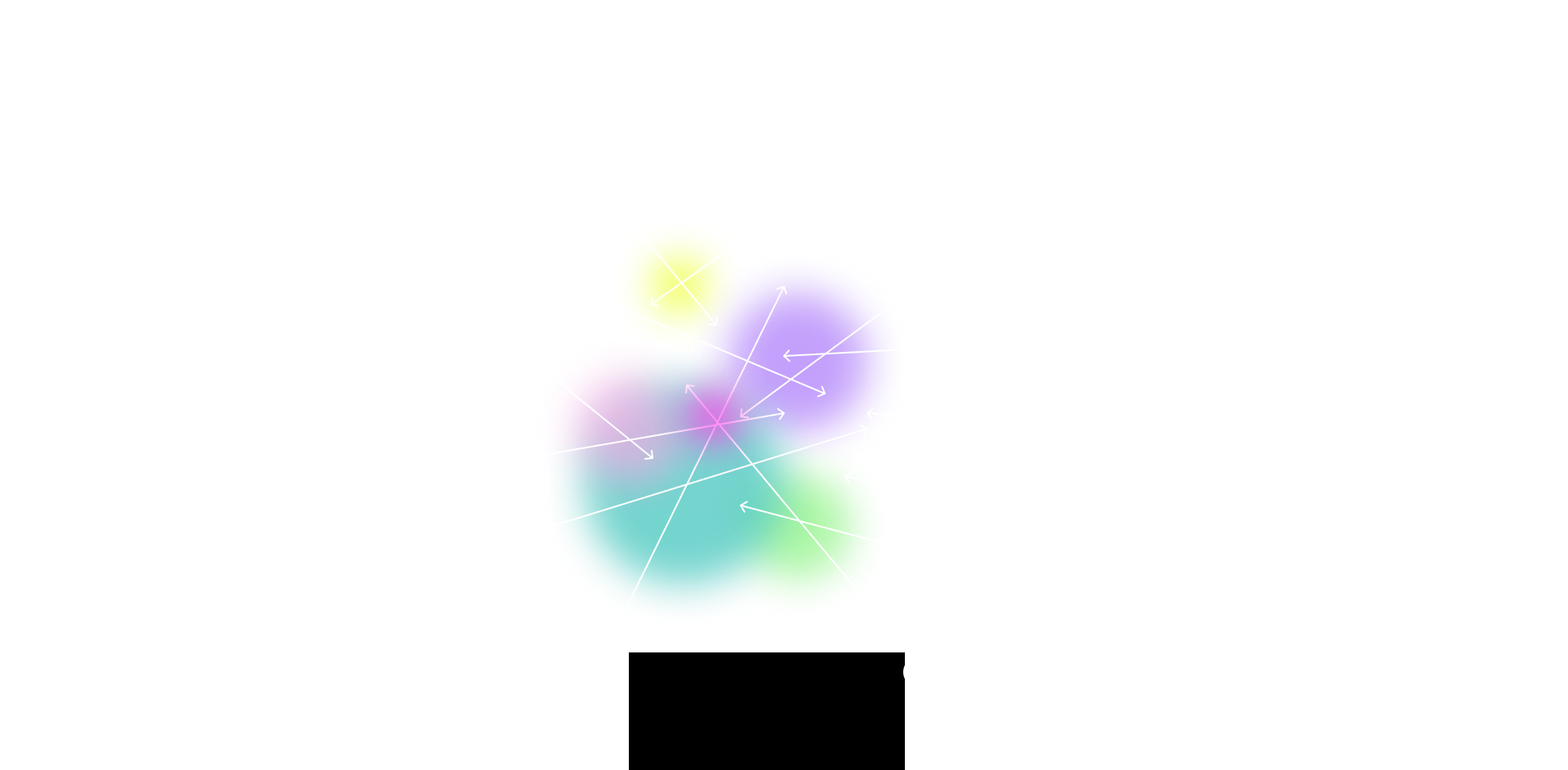

In the above model, extending our expectation of breadth leads away from the assigned focus. We can argue that this thinking can lead to a binary understanding of subjects themselves — perhaps even a limited understanding of the self. Many creatives are asked “are you a ‘systems-thinker‘ or are you a ‘story-teller‘?” The choice can be excruciating and can limit the very core understading of the interplay between these modes of thought. If we were to bend the metaphorical cross-bar of this “T” we might realize that varying levels of depth across a range of subjects result in unexpected combinations.

04

We quickly realize in this example that a common binary, math vs. art, is just a perception and our linear understanding of subjects bends. Whether the ends meet and you see poetry in science is up to you. But be it circle or spiral, we no longer see ourselves as a T-shaped practitioner, but a concentric practitioner. This mirrors less the linear, destination-based growth we tend to adopt. Instead it allows us to mirror the rings on a tree. Staying ourselves at the core, but constantly adding, growing in wisdom.

05

When these intersections happen, from all around our concentric set of interest, skills and passions, it allows us to create connections and more truly represent our unique expertise and personal story. Add to it another layer that goes beyond your job or career, simply your everyday interests, hobbies and identity. The connections begin to light up. Not only making the original T boring by comparison, but creating a unique fingerprint that is impossible to recreate.

This realization, that Creative Directors enter through a specific skill, but rely on their unique identity to become who they are has led to several questions I’ve been exploring. Over the coming months I intend to continue to fomalize the essays and experiments I've begun to develop. I’d love to collaborate with anyone in any industry who sees this exploration as way to break down any barriers of entry into the world of Creative Direction.

A Three-Part Exploration

When I was in school, I purchased “Standing on the Shoulders of Giants”, a collection of interviews by Hermann Vaske. In addition to being an accomplished film director, Vaske built a body of work interviewing the 20th Century’s most highly-lauded creative directors within advertising. The cover of the book depicts a hand holding a recording device up to Michelangelo’s depiction of God (creating the sun no less). The cover image is just a preview of the hubris inside as Vaske interviews 35 men (34 of whom are white). Subdivided into three categories (copywriters, art directors, and directors) these men share at length their story of how they made such great work. There’s no mention of their mental state while creating these works, their collaborations, their process, simply the seemingly insurmountable tasks they had before them and their ability to prevail. There’s no wisdom shared, no tips, no humility.

In reality the myth-like stature of these men is due to their great work and their perceived stoicism. Admitting fear, sadness or even a hint of imposteur syndrome would connect these great craftsmen to their millions of fans. Vulnerability has only recently come into the public consciousness as a potential strength and creative practitioners can continue to express it if not to connect to others, to be true to themselves. Generosity was a realatively new Creative Director trait when Virgil Abloh paved one of the most profound and inspirational careers on his ability to inspire and empower.

In order to explore this role more fully I believe we need to look at it through a new lens that's been blatently avoided thus far. First through the interior of the person (their identity, thoughts, dreams, emotions) and how it has influenced their work. Secondly through their unique way of working, not their inborn talents but their process and how they created it. And finally through their connection to others, the collaboration and the connections to audiences that has historically been replaced by a sense of “magic”. These are three areas of study:

Interior

Creative leaders have historically avoided personal stories and unique internal make-up as key to their success. The result is an accepted existence of an individual who has mastered a particular role. The truth is that the most creative individuals are an absolute result of their interior selves, their lived experiences, and their personality.

Synthesis

Naturally, every student wants to learn “the tricks” the “how” the proper “way” of working. And just as naturally, every practitioner that has found success seeks to “guard” their tricks due to a deep lack of confidence — a confusion between their “ability” and their “tricks.” The result is an accepted existence of an established “way of thinking.” In truth, successful creative practitioners have established their own unique way of working that could hardly be repeated. They’ve come to their place through trial and error.

Output

Great creative work doesn’t just exist. It does something. It connects and improves the human experience. But the history of creative commercial work ignores this connection for a sense of magic. The result is an assumption that the work has come from somewhere else and is handed down to an audience to bring them to a higher place. The truth is that the the answers are all around us.

Help!

If you are a Creative Director, teacher, or someone pursuing a career in any direction give me a shout, would love to talk more about these areas of inquiry!

Many thanks for their generocity. These great people allowed me to interview them 01: Yego Moravia, Creative Director Apple; 02: Johanna Langford, Creative Director; 03 Joe Staples, Creative Director, Mother LA; 04: Lyanne Dubon-Aguilar, Creative Director, Etsy; 05 Anjelica Triola 06 Gillian Haro, Creative Director, Aruliden; 07 Julia Hoffman, Executive Creative Director, Google; 08 Kevin Kearney, Founder, Stacks; 09 Randy Hunt, Head of Design, Grab; 10 Min Lew, Partner, Base; 11 Andrea Marpillero-Colomina, Urbanist, The New School; 12 Dan Schechter, Executive Creative Director, Instrument; 13 Lisa Smith, Executive Creative Director, Jones Knowles Ritchie; 14 Nishat Akhtar, Assoicate Vice President of Creative, Instrument; 15 Karin Fyhrie, Founder & CCO, Sovereign Objects; 16 Alexandra Wells, Creative Director, Media Monks.

Let’s Talk! I’m always ready to collaborate, interview and listen please get in touch ↗