2021

Systems & Stories

Let’s not choose just one of the two most powerful technologies in the world.

☻ This in-progress essay is part of a series of writing, interviews, and syllabus for emerging creative leaders. For more information please get in touch ©2021 August Heffner

Left: Our massive system photographed by Apollo 17 crew as they were traveling to the moon on Dec. 7, 1972. Image Credit: NASA Right: “Rip Telling His Fabulous Story” (Rip Van Winkle, illustration) by Felix Octavius Carr Darley, born Philadelphia, PA 1822-died Claymont, DE 1888 via Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery

What if it’s not a choice?

Inspirational creative leaders in advertising and technology have lauded the dichotomy of systems-thinking and storytelling to the point of exhaustion. The obsession with these two “modes of thinking” has driven a disturbing amount of creative people to define their identity by these technologies. The result is the deep suspicion of the speaker at the conference with the title of “storyteller” and the confusion of a designer who erroneously sees tidiness as proof of systems theory.

Humans are naturally egotistical and it's absolutely helpful for us to learn complex topics by centering them in ourselves. Unfortunately, the refusal to see stories and systems as they are limits our ability to truly study them. Quite simply they are not just personality traits, they are the two most powerful technologies in the world. It would behoove any creative professional to make sure that as they get paid, they are studying these two technologies to their fullest extent, they may just be the most important things we understand in our time on earth.

Stories are a powerful technology

Author and MacArthur Foundation Fellow Ocean Vuong has brought us the most powerful stories of our time. A poet whose childhood was shaped by war's aftermath, he reminds us that stories shape the lives of people. They are the basis for wars, nation’s building and collapsing.

“Entire nations are built on the myths of storytelling. It takes the story to harness the resources either for good or for destruction.”

—Ocean Vuong

Stories are more powerful than science or force. Listening to Vuong we understand that all the militaries in all the world are no match for a story. We see that today in America as the profound scientific breakthrough of vaccines are no match to those who have aligned with an anti-science story.

But stories don’t just move the masses, they are perpetually with us as individuals. Our identity is a story we tell ourselves. Modern therapy and cognitive behavioral studies show us that stories (yes, similar to “once upon a time” stories) repeat in our head about how our life is and will continue to be. Renowned therapist Esther Perel explains that stories we have in our own lives embolden us or keep us trapped. And these stories are rarely new. We can even see their roots in the ancient story archetypes most often associated with western myth and folklore.

As a group we might see the story archetype of “Rebirth” as the story of our time. Since March 2020 as the Covid-19 pandemic took hold, many referred to their new life of working from home to lock-downs as “Groundhog Day.” A widely accepted term originating in the 1993 film starring Bill Murry as a man who relives the same day over and over. The story has its origins not only in Dickens’ Christmas Carol, but also Dante and other ancient rituals where the hero must change something about themselves in order to break the cycle.

From left to right: An example of the “Slaying the Dragon” hero myth, “Perseus Triumphant” by Domenico Marchetti (ca. 1780–after 1844 Rome), Intermediary draughtsman Giovanni Tognolli (1786–1862 Rome (?)) after Antonio Canova (Italian, Possagno 1757–1822 Venice) 1813, British Museum; An example of the “Rags to Riches” myth, “Cinderella” (1950) original production animation drawing – red, brown and black pencil on untrimmed animation sheet © Walt Disney Studio; An example of the “Rebirth” myth, Groundhog Day (Columbia, 1993), Starring Bill Murray, Andie MacDowell, Chris Elliott, Stephen Tobolowsky, Brian Doyle-Murray, and Harold Ramis. Directed by Harold Ramis. Promotional poster.

As individuals we might be moved more by Rags to Riches, a story we have modernized into the Founders of Google (and many other companies) beginning by working out of a garage. While historically it is understood as a motivational story, Rags to Riches can serve any strata of society, where one person's “rags” may in reality be an outrageous fortune to begin with. The story is baldly employed by politicians from right and left, and drives the aspirational desires of advertising and technology to this day.

But beyond their world-changing and identity-making power, they are with us in our daily work efforts. Leland Maschmeyer, of Collins, explains his time as Chief Creative Officer during the inspiring brand turnaround of Chiobani as slaying a dragon.

We inherit the story-telling gene when we are born homo sapien. We may write new stories but they are built on thousands of years of archetypes. Storytelling is a collaborative process and one that we are both part of and have to learn to observe. All Creative Directors weave story into their process. From the director presenting a commercial treatment, to the fashion designer presenting a new season, and, most counterintuitively, the logical product designer presenting research-based features. Stories needn’t be fictional to be powerful.

Systems power everything

Equally world-shaping is the power of systems. Donella Meadows (another MacArthur “Genius”) explains in “Thinking In Systems” the biggest problems facing the world are essentially systems failure, they cannot be solved by fixing one piece in isolation. The opposite is true as well: The success of abhorrent systems (those of inequity and injustice) are a struggle to undo. And, she explains, most captivatingly, how all systems are connected.

“There are no separate systems. The world is a continuum. Where to draw a boundary around a system depends on the purpose of the discussion."

—Donella Meadows

Being a “systems thinker” is akin to saying you are a “biology-thinker” or a “digital-thinker” a near impossibility to form your way of thinking around something so important and so separate from our evolutionarily-created way of thinking. Considering yourself or your colleagues as a “systems thinker” is inevitably a dead end. It not only leaves those without this special power on the margins, it offers no inspiration for these supposed thinkers to discover more. In this purely economical view, their goal is simply to apply their perceived skill.

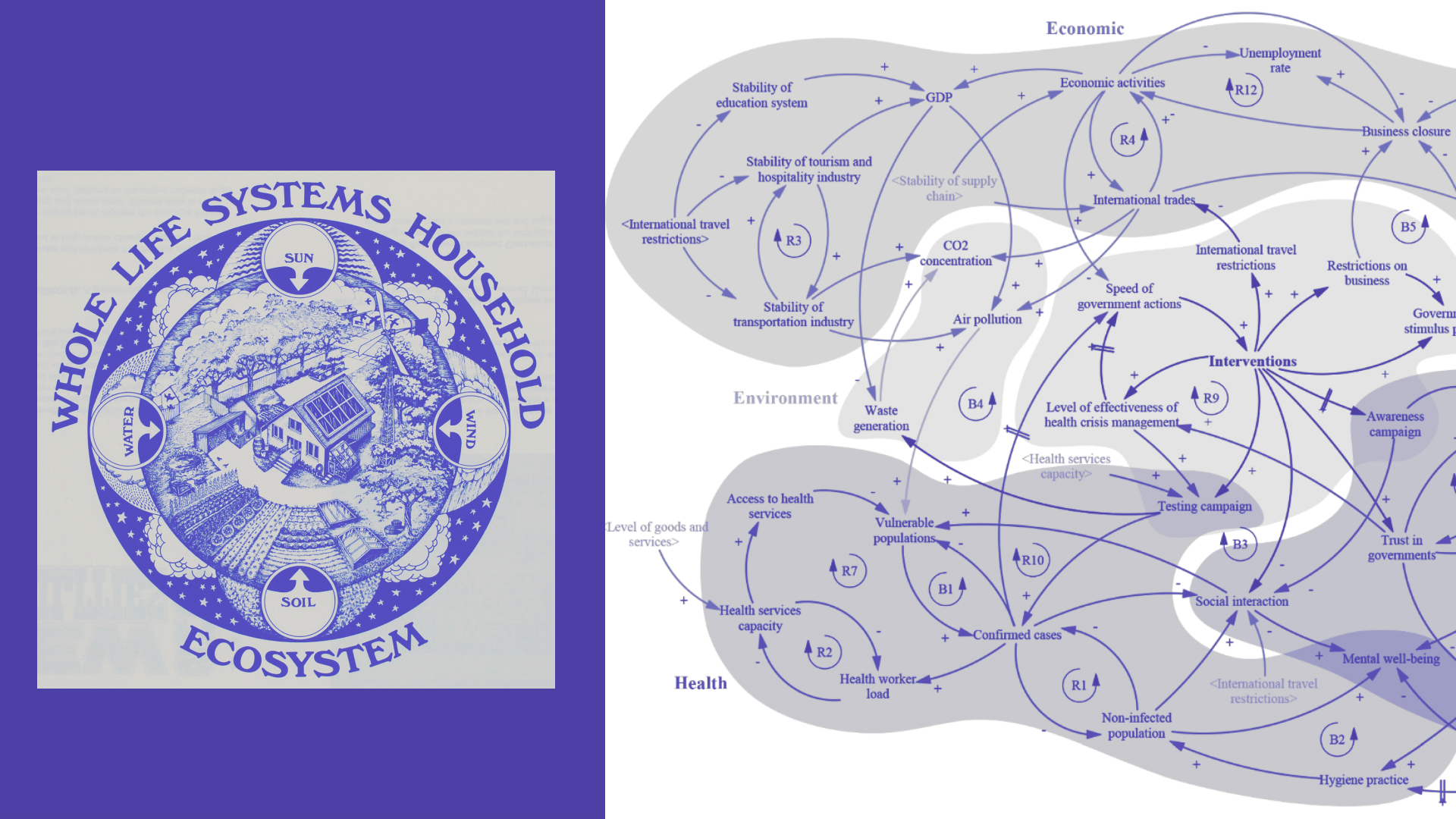

Left: The Office Of Gordon Ashby / Office of Appropriate Technology, “Whole Life Systems Household” poster work on paper Late 20th Early 21st Century All Of Us Or None Archive. Gift of the Rossman Family. © 2022 Oakland Museum of California. Right: Sahin, Oz, Hengky Salim, Emiliya Suprun, Russell Richards, Stefen MacAskill, Simone Heilgeist, Shannon Rutherford, Rodney A. Stewart, and Cara D. Beal. 2020. "Developing a Preliminary Causal Loop Diagram for Understanding the Wicked Complexity of the COVID-19 Pandemic" Systems 8, no. 2: 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/systems8020020

As incredibly fundamental as systems are, our brains rarely think in systems. They are not computers, or muscles. Science writer Annie Murphy Paul likens the brain to a magpie, a chaotic and beautiful collector of information. We can understand systems, we can diagram them and feel their effects. But we can not see them, as Yoko Ono sings declaratively: “Who has seen the wind? Neither you nor I.”

Meadow’s explains (too quietly in my opinion) that the danger of studying systems is the erronous notion that we might use them to predict. We study systems to understand them, and learning the fundamentals of stock and flow in systems dynamics allow us to, if not "see the wind," at least feel it.

Lessons in systems theory on the feedback loops that keep systems either balanced or explosive allow us, if not to predict, to harness the very elements of a system that cause outcomes. These loops are often mistaken as individual actors, design elements, or specific words that bring success or failure. But we might do better to see them as trends, parts of our work we might invent, but more likely harness, adjust, and reimagine.

Creative Direction doesn't create systems. Systems provide harmony and beauty in the details, while also powering how great works moves through the world. Every advertising campaign, digital product, line of physical products, or interior design is based on systems large in small.

Your power is in harnessing, cultivating, and educating yourself in stories and systems

We can imagine the power to apply a “systems mind” to any problem or the power to “tell a new story” that changes the way of the world. But these are imaginary superpowers worthy of the biggest Marvel movies. Like superheros they represent our internal desires and not reality. Fortunately superheros don’t make us feel bad about our limitations, they help us focus on ourselves—our power (Superman), our tools (Batman), on our responsible use of our gifts (Spiderman).

So congratulations, you don’t have to choose and you do NOT have to pass an imaginary test. You do not have to BE something else. You are a human with many superpowers and your goal is to study, employ and harness both story and system to focus our work. We must make any job, any project, any client, an excuse to harness, cultivate and educate ourselves and others on systems and stories.

Let’s Talk! I’m always ready to collaborate, interview and listen please get in touch ↗